The Land Crisis

"If a conservation organization gives us more money, we're for conservation. If a logging company gives us more money, we're for logging. If a mining company gives us more money, we're for mining."

-- Congo Basin forestry official

Millennia of Sustainability: the era of customary management

Archaeological evidence indicates that humans have lived in the Congo Basin for at least 40,000 years and when European explorers first encountered the region's rainforest in the late nineteenth century, it presented a vast storehouse of biodiversity, with abundant flora and fauna. Ethnographic data gathered since that time illustrates how local people managed their forest lands.

The rainforest landscape was divided into customary "territories" -- tracts of land large enough to provide for the subsistence needs of a local community. The members of that community were not considered to "own" the land, in the sense of having the right to alienate it, but were regarded as "trustees" of a patrimony -- a "commons" (link to The Commons page) -- left to them by their ancestors, in accordance with the land spirits of the locality. The fertility of the land depended upon maintaining harmonious relations with these spirits and among the members of the community itself. The resources of the land possessed value by virtue of their ability to provision the members of that community over the generations, along with the other species with whom they shared the forest.

Enter the Europeans: the colonial extractive economy

Historical evidence suggests that a similar logic guided the relation of people to land in Europe (link to The Commons page) during the majority of its history. By the nineteenth century, however, European conceptions of land and economy had changed dramatically. The fruits of the land no longer had value simply as a means of provisioning human communities over time, but by virtue of their ability to be inserted into networks of global trade and generate European currency.

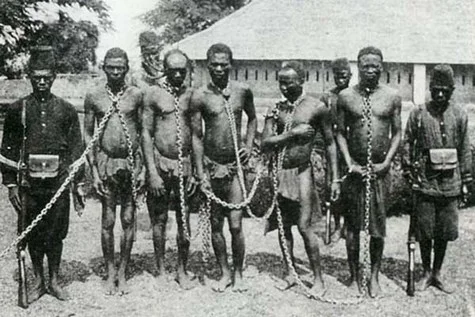

Once the armies that followed the explorers succeeded in crushing local resistance to European intrusion, colonials converted the Congo Basin landscape into a set of "colonies," each of which was administered by a central government. As one of the cornerstones of the new social order, laws were passed declaring that all uncultivated land -- i.e., the vast majority of the rainforest -- was the property of the colonial state, to do with as it saw fit. Each colony was then divided into "concessions:" enormous tracts of land that were leased to large commercial enterprises from the home country for the purpose of extracting the resources that were of value in European markets; in the rainforest, the primary items sought were ivory and wild rubber.

In order to procure and transport these valued resources, a brutal regime of forced labor was introduced, in which locals who refused to comply with colonial labor demands were subjected to beatings, imprisonment and, in some places, amputations.

As a result, the colonial extractive economy produced considerable suffering for local peoples over several decades. In addition, although its ecological effects were limited, the institutional framework it established set the stage for the current crisis.

A modern compromise: the development regime

After World War II, the extractive economy was replaced by an economy oriented towards "development," which focused on cash-crop production. The brutal regime of forced labor came to an end and the system of land-use was transformed from one centered around the large-scale concession to one based on the local farmer's agricultural plot, who raised cash crops (coffee, cocoa, etc) for export.

Once independence came in the 1960s, this same economic model remained in place and local peoples managed to reap some modest benefits from their participation in international trade, allowing them to procure basic goods and services -- clothing, health care, education for their children, etc -- as well as provision the central government through their tax revenues. With a stable export economy in place, several countries in the Congo Basin enjoyed a degree of relative prosperity and political independence, while local people gained basic access to modern goods and services. In short, the independent countries of the region had become functioning modern nation-states.

Things Fall Apart: the debt regime

In the 1980s, however, all this changed. As the post-war boom in the global economy came to an end, various forms of economic turbulence were introduced and global prices for the region's cash crops collapsed. Lacking the steady flow of foreign exchange from the development era, and with their tax base eroded, regional governments soon fell into arrears and were forced to take out loans from international financial institutions to survive. But as the export economy continued to be depressed, a regime of international debt came to be the "new normal" for the countries of the region. This debt regime has had drastic consequences for the governments, citizens, economies and environment of the Congo Basin.

The responsibilities that regional governments had toward their citizens ceased being a political priority as they were now responsible primarily to their creditors at the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). As these institutions began attaching austerity measures -- referred to as "structural adjustments" -- to the loans they made to Congo Basin countries, regional governments were obliged to accept them. These, in turn, produced massive unemployment, devalued currencies and general economic collapse.

In the throes of economic crisis, with their tax base severely compromised, regional governments scrambled for any possible means to produce revenue. With a legal framework giving them management authority over all uncultivated land in their national territories, and with rich timber and mineral resources at their disposal, governments turned to extractive industries to solve their financial problems. The colonial model of revenue production was revived, the forest was divided into large-scale concessions and these were leased to international logging and mining companies. In the process, not only were colonial structures of land management reinstated, but the Machiavellian approach of colonial governments toward natural resources was restored, in which revenue generation outweighed all other concerns. As a high-level forestry official in one Congo basin country put it:

"If a conservation organization gives us more money, we're for conservation. If a logging company gives us more money, we're for logging. If a mining company gives us more money, we're for mining."

At the same time, a consensus emerged among international policy-makers -- the World Bank and the IMF, the governments of the United States, France, (Britain), (Belgium) and Germany -- that the most effective policy for the Congo Basin rainforest was an economy based on extractive industries to generate revenue, supplemented by a series of "nature reserves" as a gesture toward environmental protection. As a result of these national and international policies, 440,000 km2 of rainforest is currently under logging concessions, an area the size of California.

This logging activity has had various negative impacts. First, industrial logging removes tree species that local peoples depend on for their livelihoods and for the fabrication of traditional medicines. Second, it compromises both game populations and fisheries due to the ecological disturbance and habitat loss it produces. Third, logging roads open up remote forest areas to other forms of commercial exploitation. By connecting forest lands to regional and national markets, the pressure on animal populations increases dramatically, as commercial hunters from urban areas come to satisfy the new demand for game meat. Animal populations which have always supported local people sustainably are unable to accommodate the increased demand and are quickly diminished, removing key protein sources from local diets and compromising the health of local people. Additional secondary effects of the logging economy include: deforestation, urbanization, corruption, illegal logging and others.

Not surprisingly, the devastating impacts that logging has on their lands and livelihoods produces resentment on the part of locals. Yet if they try to resist, security forces -- either state-sponsored or privately contracted -- are sent in to crush the resistance. Since logging taxes make up an important part of state revenues and logging companies make "unofficial" payments to government officials at all levels, the state considers local resistance to be an impediment to the smooth functioning of the national economy.

The use of security forces to quell local resistance is also a prominent feature of the strategy that policy makers chose to protect the rainforest environment. When nature reserves, referred to as "protected areas" (PA's), are created, the local communities whose forest territories fall within the zone earmarked for protection are forcibly removed from their land. In addition, foreign conservationists, with their single-minded focus on the protection of endangered species, tend to see all local peoples as potential "poachers" and employ well-armed poaching patrols to keep them from carrying out subsistence activities on their land. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for poaching patrols to take advantage of the power that superior weaponry affords them by going far outside park boundaries to harass local villagers, confiscate their food and sell it in regional markets.

As members of local communities are forcibly removed from their traditional lands, their access is barred to their sources of daily subsistence, and they are harassed, beaten, tortured and even killed by the well-armed enforcers of what has been described as "fortress conservation," they come to harbor a profound resentment towards the conservation agenda. As one villager put it:

"Our ancestors suffered at the hands of the French. We suffer at the hands of the conservationists."

In this way, the zones surrounding protected areas are plunged into a state of psychic war between locals and conservationists, which occasionally erupts into violent confrontations. Given this state of affairs, when actual poachers are operating in PAs, locals fail to report them, allowing their activities to be carried out uninterrupted. This silence, coupled with the fact that organized poaching gangs make unofficial payments to government officials to avoid prosecution, means that poaching remains a viable enterprise despite the firepower that is placed in the hands of conservation organizations. These various factors combine to produce one of the crowning ironies of conservation in the Congo Basin: as a recent study drawing on data from thirty-four PA's in the region shows, not only do they result in destructive impacts and human rights abuses for local communities, they fail to protect the very animal populations they are designed to preserve.

Towards a workable solution

Westerners operate out of a linear conception of history and find comfort in the belief that things improve over time. In the Congo Basin, however, the present has increasingly come to resemble the colonial past: a social order centered around the extraction of local resources for outside benefit, in which violence -- sponsored by states and powerful foreign organizations -- is commonplace. The colonial regime of forced labor has not been reinstated, but it has been replaced by something even more destructive: the impoverishment of the land and the destruction of subsistence economies.

For at least 40,000 years, land management was in the hands of local communities and the forests visited by Stanley and others in the late nineteenth century were rich with wildlife. Given this, it is remarkable that national and international policy-makers now act as though local communities are irrelevant to larger policy agendas and lack any legitimate rights to the lands they have managed for millennia. Such a view of the inhabitants of the rainforest -- as irrelevant to, and even "enemies" of, the "real work" of forest management -- is what underlies the fortress conservation approach currently employed by the majority of conservation organizations working in the Congo Basin. Not only is it grossly inaccurate in historical terms, it is fundamentally objectionable in regards to human rights. Furthermore, it is profoundly impractical as a strategy for accomplishing the professed goal of international conservation: preserving the populations and habitats of endangered species.

The current strategy is to employ small teams of well-armed "eco-guards" and an aggressive, zero-tolerance policy toward anyone even suspected of hunting in PA's. Yet these areas cover vast expanses of forest and it is logistically impossible for a few poaching patrols to properly police them. The only way to effectively patrol such spaces is to enlist the assistance of those who already live in the area and are disbursed throughout the environment. This would require conservation organizations to recognize the customary land rights of local communities, but if a social contract could be created between the two parties, giving locals a chance to earn a living as guardians of their forest territories, they would jump at the chance. After experiencing the devastating impacts of logging and watching outsiders come to take their resources, they would like nothing better than to have outside assistance in their efforts to protect their traditional land.

At a historical moment in which the international community has recognized that it needs healthy tropical rainforests to help mitigate against global climate change, it must also recognize that it needs healthy local communities to take care of them. Yet such an undertaking would require not only a new, collaborative approach to conservation, but also a much larger effort to find means other than extractive industries to keep the governments of the Congo Basin solvent. If the international community truly seeks to maintain the ecosystems of the Congo Basin rainforest as a hedge against climate change, they will have to muster both the courage and commitment to find ways to bring the economies of the region back to the stability they enjoyed during the years of the development regime. Only in this way can international goals for the rainforest environment be effectively realized and a true regime of "sustainable development" put in place.